Here's the text of my award-winning Merton article. Big thanks to Dennis Sadowski at the Catholic Universe Bulletin for indulging my interest in the subject, and to Ann Augherton, managing editor of The Catholic Herald in Arlington for running a slightly different version of this story.

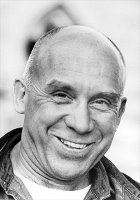

Thomas Merton: Leading us toward the contemplative life

By Wendy A. Hoke

Catholic Universe Bulletin

Nov. 18, 2005

He was only 53 when he died, and had only been a Catholic for 30 of those years, but Thomas Merton found a way to touch the contemplative within all of us.

Most Merton scholars agree it was his transparent yet imperfect search for grace, his introspective, powerful writing, and his interest in the ecumenical that calls people of all faiths to his work.

His writings are often found in today’s religious literature, regardless of faith orientation. Many believe he is a good contemporary example for Catholics. But he will not be part of the new official American Catholic Catechism because for some he was too contemporary, too imperfect.

For the struggling and the searching, however, he has been a welcome voice for nearly 60 years.

First published in 1948, his autobiography “The Seven Storey Mountain” became a bestseller at a time when religious works were not included on the New York Times Bestseller list. Worldwide, his autobiography has sold multiple millions of copies, having been in continuous publication. His body of work has been translated into 29 languages, including Indonesian, Turkish and Croatian.

Merton’s international reach goes beyond publishing. His writing is the touchstone for interfaith discussions, a form of literary advocacy for social justice and peace and the very embodiment of his quest for the divine while struggling with being human.

“It’s not anything immensely new, but Merton has interpreted the spirituality of the Catholic Church in a way people can understand and with some depth to it,” said Paul Pearson, director of the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Ky.

He was an ordinary man struggling with his own spiritual life, but his willingness to share that struggle so openly mirrors our own.

How does a monk manage to capture contemporary life? Because he brought with him significant life experiences. Merton was born in the 20th century, lived through war and was educated in different religions. Before converting to Catholicism, he lived a Bohemian New York lifestyle. “He had an enormously broad vision of society and the world even within the confines of the monastery,” said Pearson.

“He felt that being a Christian, even being a monk, you have to be engaged and educated about what’s going on so you can have a response—either in an active or contemplative way,” said Erlinda Paguio, president of the International Thomas Merton Society (ITMS), also based in Louisville. He was honest and open in his search for God, in his search to become whole.

Merton’s legacy

Educated at Columbia University, Merton could tap into the well of the intellectual and the ordinary person, said Ursuline Sister Donna Kristoff, president of the Cleveland chapter of the ITMS. “He read Joyce and Sartre and he understood the 20th century politically and culturally,” she said. He did that through a network of friendships and vast correspondence that kept him very well informed.

But being removed from the world also gave him a wider perspective and a bit of distance for observing everything from the Vietnam War to Civil Rights movement.

Merton, who is not without his detractors because of his humanity, has been referred to as a lapsed monk primarily because at the end of his life he was engaged in dialogue with Eastern and Western monks.

Pearson believes he was simply living what Vatican II suggested—talking to others about their faith while firmly rooted in your own. That’s what his writing shows when he died tragically on Dec. 10, 1968 in a Bangkok hotel room, having been accidentally electrocuted.

Sister Donna Kristoff remembers picking up a thin book with a burlap cover while a senior in high school. It was Merton’s “Seeds of Contemplation.” “I remember reading it in an hour and thinking how beautiful it was.”

She entered the convent the following September, but was not exposed to him there. An art teacher, she eventually wrote a paper on Merton and icons. “He had a gift for translating a lot of ancient traditions into modern language. He was pious and austere, but he also showed there was a human person behind the contemplative,” she said.

And he left room for people to find their own way toward contemplation.

Finding Merton

“People come to Merton through all sorts of rooms,” said Jonathan Montaldo, former director of the Merton Center and editor of the recently published “A Year with Thomas Merton.” Many are drawn to the spiritual Merton, others are interested in his insights into Buddhism, others love his photography and many love his literature, he said.

By tapping into the primary sources—the desert fathers and mothers and mystics—he revived the early church writings and built on that wisdom, making connections to the wisdom of Zen and hermit history, Sister Kristoff said.

Regardless of how he is discovered, his impact is lasting. “Merton’s ability to leap forward to communicate to new generations amazes me,” said Montaldo.

Sister Kristoff agreed. “He opened the avenue of contemplative prayer for the ordinary person, a movement that has experienced renewal in the church,” she said.

Merton recognizes that spirituality is not an ideal situation. It’s filled with both light and shadow. “Merton’s talent is that he wrote in order to find God in his own experience, not in someone else’s,” said Montaldo.

Contemplation, Merton believed, is for everyone and he was criticized for that belief. But that was also his gift.

“Merton recognized the face of God in everything. He knew it theoretically and experientially and that’s why his writing has authenticity and power, and why he continues to be read,” said Pat O’Connell, editor of the Merton Seasonal and professor of theology and English at Gannon University.

“He doesn’t pontificate answers from some elevated eminence. The fact that he’s flawed and admits it makes him so much more meaningful,” said O’Connell. “He is Catholic with a small c and big C. He’s very faithful to the religion and someone who saw that religion as a way to open up to the universality of all humanity.”

Monsignor William H. Shannon became editor of his five volumes of letters and said Merton helped him to realize, “Contemplative life is human reality, not just monastic reality,” he said.

Some of his work could even be considered prophetic. “Last year we saw publication of ‘Peace in Post-Christian Era,’ which was banned in 1962,” said Pearson. “Though we are no longer talking about the Cold War you can substitute terror or Iraq for communism because the overall picture hasn’t changed.”

“Like any good writer, he speaks to you in different ways at different times,” said Shannon. “He was a born writer. Fortunately, he had an Abbott who recognized and encouraged him in his writing.”

Many Merton scholars believe that he did not want to become a myth for children at American parochial schools. He did not want to be an idol or guru with a following. But his contemporary messages seem more important today than ever before.

“Merton's writing … is a source of unity, a bridge for Catholics and all spiritual seekers to cross over and find a common ground in the search for God through their ordinary lives,” said Montaldo.

Sidebar

Pilgrimage to Bellarmine

The Thomas Merton Center is an archive based at Bellarmine University, a small, liberal arts Catholic College in Louisville, Ky., near the Abbey of Gethsemani, the Trappist monastery where Merton lived.

Though there are also collections at Harvard University and St. Bonaventure, Bellarmine remains the official repository. Started by Merton in 1963 when it was suggested he find a home to deposit his many manuscripts, the Merton Center is currently home to 50,000 items including photos, drawings, calligraphy, manuscripts and journals. There are 20,000 letters of correspondence with 2,100 individuals. It contains 260 doctoral and master’s theses and 1,400 photographs.

The center’s mission is to preserve and collect materials related to Merton’s life and work. Just this year, it acquired 14 calligraphies and some more letters, according to Paul Pearson, director of the center.

“We’ve reached the point where all manuscript material has been published. But we’re never quite sure because something new may come to light,” he said.

Merton was a prolific letter-writer and the center has entire sets of correspondence from some individuals. It also contains large exchanges with his publishers, with Dorothy Day, a Muslim scholar in Pakistan and with Latin American poets.

The center is open to public from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday. Visit www.merton.org for more information.

The local chapter of the International Thomas Merton Society meets at 7:30 p.m. the third Tuesday of every month from September through May at Ursuline College Mother House.

1 comment:

Shalom Wendy,

Thank you.

B'shalom,

Jeff

Post a Comment